Death Valley: Part Two

It was a little over 120 degrees the first time I went to Death Valley. On purpose.

In 1999, I made a cross-country move from Boston to Los Angeles. Soon after, I got fairly settled into California life. I’d secured a good job, met new friends, had a nice place to live, and all the things you typically hear someone say when they’ve started a new life. But it didn’t feel the way I thought it should. Up to that point, most of the things I’d accomplished had involved other people’s help; Mom, Dad, friends, co-workers, the Cosmos… 🙂 There’s absolutely nothing wrong with that, and a more sane person probably would have been very content with that life.

But not this Moonbird.

I was feeling restless and wanted to put myself in a situation where I would only have me to rely on. So I designed a “rite of passage” where I would have to survive something challenging all by myself. I decided to hike the dunes in Death Valley solo. In August. When it was 120 degrees (48.8 celsius). I also wasn’t going to tell any of my friends or family what I’d done until I’d gotten back.

It’s funny, because writing this out now, the craziness is so clear. Can’t say I’ve always made the best choices. 🙂

Long story not real short, I did some research about desert hiking and found a man in the Southwest who had been doing just that for many years. I sent him an e-mail and told him my general plan without giving any specific dates and times. I didn’t want anyone to know the nuts and bolts. He wrote me back that same day, and I’ll never forget his response. He said:

“Hello Daniel! Thanks for writing. I’d love to begin this e-mail by telling you that the answer to your questions is simply not to go in August, and certainly not alone. However, I can also tell by your e-mail that you’re crazy in a good way, and not going to wait, so let me at least help you stay alive. First thing you need to know, and this is crucial, is that it’s not a matter of *if* you get dehydrated… it’s a matter of when.”

He then offered a lot of great tips about survival, what else to pack, first aid, how to plan my food for the kind of trip and more. He stressed the importance of caloric and nutritional balance to maintain energy while in such an extreme environment and what the signs of dehydration are. In my additional research, I also learned a lot about how and why the body sweats and how much water to carry. In this case, that was more than two gallons, plus a 32 ounce Nalgene reserve bottle. Twenty pounds of water before any other gear.

I was also bringing my 35mm film camera (this was before digital was big), tripod, food, change of clothes, trekking poles, and first aid and snake bite kits. I purchased a pair of wicking pants from REI, a good sunscreen, and then I wrote a time-delayed e-mail to a friend I trusted. If something bad happened, it would be sent to her the day after I was supposed to be back, and said something like, “If you’re reading this, I’m likely in trouble, or maybe dead, and here is where they should immediately look for me.”

I want to reiterate at this point, that in all seriousness, unless you’re mental, I don’t think you should ever do what I did. What follows, is why.

I left Los Angeles at the crack of dawn and drove four hours or so to the park. I went right to the sand dunes, thinking I would hike them for the first day, find a place to sleep, enjoy the desert at night by myself, and then hike the next day and see where it took me. I got out of the car and after smiling ear-to-ear at the amazing view, began my gear check. Backpack, camera, batteries, film, tripod, water bladders, water reserve, trekking poles, first-aid kit, and clothes. Check. I covered myself in sunscreen and made sure my boots were laced correctly. Then I put the forty some pounds of gear on my back, donned my trusty Indiana Jones style hat, and headed out into the desert.

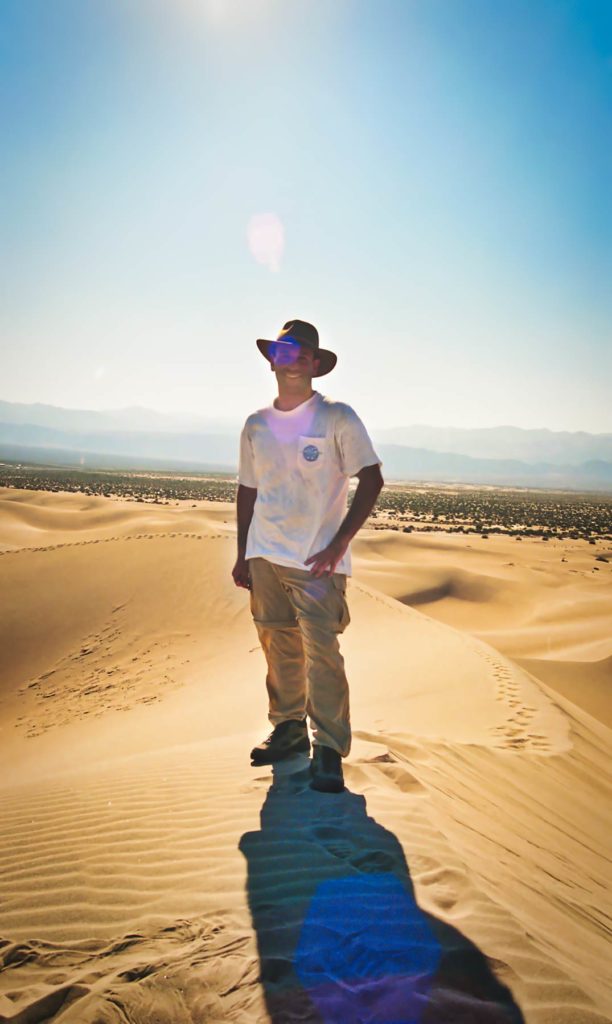

It was gorgeous. I’d stop every twenty minutes or so and take a picture here and there. As I mentioned, this was back before digital and I was shooting on 35mm film with only 36 exposures per roll, so I tried to persevere my shots. Here’s a selfie (before the term existed) I shot with a timer on my tripod. My big pile of gear was out of frame, but you can see the sweat marks from the backpack on my shirt.

Self-portrait, Death Valley sand dunes

I kept hiking and eventually, after a couple of hours, had made my way into the deeper part of the dunes. I couldn’t see my car, or any civilization, no matter what direction I turned. I decided to take a break and rest for a few minutes. A snack sounded really good at that point. Per the advice I was given, I had packed specific foods perfect for that kind of heat and energy exertion. I dug around my pack for a minute, and then felt a big knot in my stomach.

I’d left my entire bag of food in the car.

I looked out at the desert before me, my tracks going back the way I’d already hiked for some time, and after thinking about it for several moments, made the next really bad choice of the day, and said aloud, “Well, this is just another part of the challenge.” Then I got up and kept going. Away from my car. Away from my food. Away from a decent amount of sanity and common sense.

A couple more hours and I’d made it to the area where the largest dunes were. I wanted to climb to the very top of the tallest dune. You know… because exerting even more energy in ridiculous temperatures with the weight of a couple of small children on my back and no food wasn’t enough of a challenge. The next thing that went wrong, was that I was simply inexperienced in desert hiking. I hadn’t ever been in deep desert sand before and didn’t know what that was going to entail. I’ll explain, because it’s not like walking on a beach. Desert sand like that is finer than beach sand. Because of this, your feet sink further than they normally do. The higher I climbed, the deeper my feet went, until with each step, my feet were now sinking past my ankles. The sand poured into my boots, and then I had to lift each boot up, carrying the extra weight of all that sand, plant another step, continuously sinking past my ankles, and repeat that slowly, over and over.

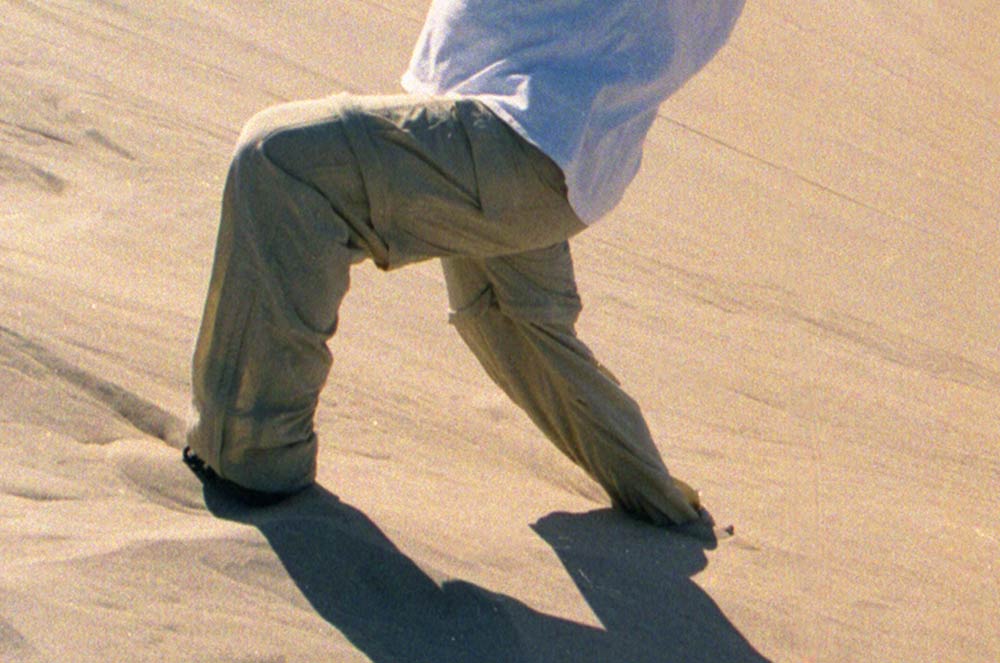

It was exhausting. Furthermore, because as I said, I didn’t know what it was going to entail, I also didn’t think about the fact that sand gets extremely hot, and the sand in Death Valley had been beaten by a 120 degree temperature and direct sunlight all day long. This meant that with each step I took, as my feet sank, even though I had socks on, the sand burned my ankles. I took one picture on a timer as I climbed a dune so people would see what I meant, but even this photo doesn’t show how deep the sand got.

The agony of “da feet.”

You’d think I would have turned around at this point, but I was determined to get to the top of that dune. Once there, the plan was to stop and rest, hopefully find some shade and wait for sunset to get some sleep. Then begin another day. I continued and eventually made it to the top. I took a break, shot some pictures, and even had the sense of humor to snap this one:

Where’s Daniel?!

Then, in my continuing lack of basic wisdom, I decided it would be fun to slide down the backside of this amazing, tall dune, more than one hundred feet, to the desert floor. It would be a fun ride! I sat down, put my gear in my lap, gave myself a whoosh and started attempting to slide downwards. Then the sand caught me, I almost flipped over, was about to go tumbling, and had enough reflexes to get myself upright, but with so much momentum, had no choice but to keep moving forward and run down the rest of the way until I could slow down and catch myself. I got to the bottom safely, and was smiling and fairly proud of myself for not face planting. Then I looked up.

I realized I was surrounded by the tallest of all of the sand dunes and had just dropped myself in a valley. I was also starting to feel pretty beat, and decided I should head back to the car for safety. I know getting back there was still going to take many more hours of hiking. Now I had to decide which path to take. There were only three ways out of this valley. One, go back the direction I’d been hiking all day. Two, loop a new path off to my left. Three, look a new path off to my right. Since the latter two options were unfamiliar, I decided to hike back up the tallest dune I had just come down and retrace my steps.

After making sure I had everything stowed and ready, I started my uphill climb. The same routine began, Foot disappears beneath the sand. Boot gets filled. Lift the weight of the hot, sand-filled boots, and my tired feet, and step upward. The one small miracle was that this side of the dune was now in shade. My thermometer still read 118 degrees. The sand on this side of the dune was even thinner, more of it was getting in my boots, and now I was fighting my way up a steep incline. I didn’t know how worn down I actually was, and ten minutes later, after I moved out of the shaded part of the dune, all of the days’ bad choices coalesced.

I was more than half way up the dune. The sun was beating down on me, and I didn’t know it at the time, but I was extremely dehydrated. I started getting a little light headed. I remember looking off into the distance and wondering why things were a bit wobbly. I also felt like I had a fever and it was getting hotter and hotter every second. Then… I suddenly felt my heart change, like it was slamming into my ribs over and over and over and over.

A few seconds later, I collapsed onto the sand.

What’s interesting is that what followed is still crystal clear to me. I remember laying there on my side covered in sand and being slightly disoriented. I wondered if I was having a heart attack, but knew enough of those symptoms to discern that I likely wasn’t. I thought maybe it was heat stroke. What I did know, somehow, was that I had two choices: get up, or lay there and probably die. I clearly saw just those two singular paths open before me. I knew I could just lay there and go to sleep, let it all go, and let the Universe decide what to do with me. I could also just get up.

I reached for my water tube. I put it in my mouth, even though it had sand in it now. I tried to suck some water out and it was empty. I laid there another moment or two and remembered I had a reserve thirty-two ounce Nalgene bottle on the side of my pack. I couldn’t believe I’d already gone through more than two gallons and not really had to urinate all day. If I wanted to access the reserve bottle, I had to move. It was positioned on the side of me that was now nestled in the sand. I grunted and groaned and got myself to my hands and knees, head still sunken. Then I heard a trickling sound. I looked up and realized two lines of sweat from both of my temples were meeting in the middle of my forehead and rapidly dripping off my brow. I’d never seen myself sweat this much or so quickly.

I was finally able to reach over and grab my Nalgene bottle. I was excited that I had thirty-two ounces of life-saving nectar! I was fairly low on strength, but with some effort, was able to twist the top open. It started steaming. The bottle had been outside my pack all day and had been heated by the sun continuously. To survive this whole mess, I was going to have to essentially drink hot tea in extreme heat in the middle of some kind of heat stroke. It was ridiculous. I couldn’t believe how many mistakes I’d made and how much had gone wrong. I sat there, watching the steam rising from the water and honest-to-God… I just started laughing.

I laughed and laughed, and after a good solid minute or so, knew it was time. I drank several sips of the hot water and it was as you’d expect it to be. Way too hot and pretty unpleasant. It also tasted a little like warm plastic and a lot like wounded pride. I poured some on my head to try and cool myself off. I left half the water in the bottle for later. Then much like a doe learning to walk, made myself finally stand up, albeit a bit weak. One step at a time, I headed back to my car.

The going was slow, and it took until just before nightfall for me to get back to my vehicle. Thankfully, I had five gallons of water in the car, and of course… a very nice bag of food. 🙂 I threw off my gear, collapsed onto my seat, blasted the air conditioning and began rehydrating. I slowly ate a sandwich and some Oreo cookies and they tasted better in that moment than they ever had before.

After stopping at the general store for some ice and cold water, I went to check in at the motel, but they were booked up. My choices were to sleep in the car, pitch a tent for the night, or drive the four hours home. I decided that for safety, I’d start the drive home, that way if something went wrong, at least I’d be closer to a hospital. Thankfully, as the food, cold water, and air conditioning kicked in, I quickly recovered from what I later found out was a bad case of heat exhaustion. I got home that night, cleaned up, canceled the e-mail I had time-delayed, and headed to bed for a well-deserved night’s sleep.

There was one amazing thing that came out of it all. Well, two. One, I did accomplish what I’d set out to do, in that I survived something challenging, relying only on myself. But even cooler, kneeling there in the desert, coming out of the disorientation after I’d had some water and felt some of my strength begin to return, I actually did yell, at the top of my lungs, “Father! The sleeper has awakened!”

For a nerd like me, that was a pretty sweet moment. 🙂

Muad’Dib, a.k.a. Paul Atreides from “Dune”

Over the years that followed, I took several people to Death Valley and explored many more of the park’s features with them. If you’d like to hear some more fun and amazing stories about those trips, and very special little fox… click on over to Part Three of my Death Valley series of posts. There’s some really cool stuff in parts three and four!

In summation, while it’s fun to tell this story, I want to reiterate that this was a bit of a foolish thing to do. Please trust me, there are far better ways to find yourself than risking your life. That said, I’m glad I did it. I learned a lot and it’s been with me ever since. If anyone ever contacted me about doing their own extreme solo desert hike, I’d tell them: “Hello! I’d love to begin this by telling you that the answer to your questions is simply not to go, and certainly not alone. However, I can also tell that you’re crazy in a good way, and not going to wait, so let me at least help you stay alive. First thing you need to know, and this is crucial, is that it’s not a matter of *if* you get dehydrated… it’s a matter of when…”

Moonbird’s Helpful Info:

Death Valley National Park

Website: www.nps.gov/deva/

Location: Inyo County, California

Google Maps: Click here

Best time to visit: Anytime. Summer months are extremely hot.

North America’s Seasons are: Spring: March, April and May, Summer: June, July and August, Autumn: September, October and November, and Winter: December, January and February.